Khoon Ke Aa'nsoo

Khoon Ke Aa'nsoo

Savitri had neither heard nor known anything like this in her life before. Most people alive in the day had never experienced such a scenario. Roads that had been bustling with traffic until last week now lay deserted, factories that had incessantly spewed smoke for decades did not so much as stir now. Daily wage migrants thus bereft of work had started to walk home hundreds of miles away. Savitri had nowhere to go. After her intercaste marriage with Mukesh, the two of them had been banished from their village forever. Not that they were issued a formal letter of banishment or anything. It had been quite informal in fact. With Savitri's family baying for Mukesh's blood the newly married couple had run for their lives in the middle of the night. They had clambered up the first train moving out of the station and had since then never looked back on the village of their birth. Come lockdown and the owner of the factory in which they worked turned off the electricity and the water taps to the tin sheds in which the workers lived with their wives and children. Mukesh, Savitri, and their two children, all of two and five years old, spent two exhausting days in their tin shed before Mukesh managed to procure another lodging for his family. It was in connection to their new lodging that Neera came in contact with Mukhesh and Savitri. The place where they shifted belonged to a friend of Neera who was at the time abroad and had been looking for a caretaker for his deserted bungalow. Neera's job was to hand them two keys. One key belonged to the Bungalow so that they could dust, broom, and mop the interior, manicure the lawns and tend to the flower beds. The other key belonged to the room at the far end of the lawn where Mukesh was to put up with his family.

The first time Neera saw that room was a month after Neera had handed over the keys to Mukesh. The room was completely barren. There was nothing to indicate that a couple with two small children had ever lived here. No splattered masala on the wall, no mark of a cooking burn on the floor; just a stale smell that lingered in the air and almost choked Neera as she opened the door. The room's brevity shocked me. It was a six by four feet cuboid that Mukesh and Savitri had been incessantly grateful for having gained access to. On the wall opposite the door was a square window. Outside the window was a shadowy patch of the garden. The ground was strewn with dry leaves, weedy plants had sprouted at random places, and what must have been a flower bed once now lay in ruins. In such profound neglect stood the Witch Hazel in all its glory. Its yellow-flowered branches seemed to invite one and all into its embrace. This entrancing sight must have been Mukesh's last. But who can appreciate the splendidness of nature on an empty stomach? Five days into the lockdown Savitri began to run out of the ration. Distressed, she called Neera and she asked her to come over to her place so that she Neera could give her some ration and money. Savitri and Mukesh patiently fed their children some watered-down dal that night and went to bed on an empty stomach. The next day during the relaxation hour Savitri set out for Neera's place. Those were the days when the officials had been overperforming their assigned duties. Savitri had barely walked down a couple of kilometres and reached the main junction when without so much as asking her the reason for leaving her house they began to hit her with a baton. Savitri fell on her knees and pleaded with the guards to listen out to her but to no avail. Limping, she retraced her steps. Back home the faces of her hungry children broke her heart.

Mukesh tended to her injuries with salt and warm water then applied a paste of turmeric on castor leaves and wrapped them around her knees. The next day as soon as the curfew relaxed Mukesh set out for Neera's place taking a less-travelled route along the canal. It was longer by about three kilometres but being a deserted stretch it was free of surveillance. Mukesh reached Neera's place drenched in sweat and exhausted. Maintaining the mandated distance Neera gave him food, dry ration, and five thousand rupees sent by her friends - the owners of the bungalow. Mukesh thanked Neera and left as hurriedly as he had come, but when Neera walked into the balcony and looked down on the road Neera saw Mukesh standing under a tree and gobbling down food the way only a man hungry for two days could.

An hour and a half later Savitri called Neera - sobbing uncontrollably. Mukesh had taken the same canal route back home. On the way, he had been apprehended by a gang of robbers who snatched from him the dry ration as well as the five thousand rupees. When he tried to fight back they beat him up until he begged for mercy with folded hands. Needless to say, Mukesh had reached home to children wailing with hunger. Neera could hear their wails over the phone as Savitri talked to me. She sounded incredibly weak and on the verge of collapse. Neera was aware of some groups of volunteers who had taken up the task of ration distribution to needy families. Neera contacted them with the hope that they might be able to deliver some ration to Mukesh's family. It turned out that due to half a dozen positive cases in the locality in which Mukesh lived the group had not been able to get permission for distribution. There was strict monitoring of movement in and out of the locality but if somehow Mukesh could make it to their godown five kilometres away they would give him the ration.

That night once more they fed rice starch to the children. It left their hunger far from satisfied but at least they would not survive. As the night progressed Mukesh's injuries came to life. He tossed about in pain. There was no more salt and turmeric to be applied to his injured muscles and bones. In the morning as soon as the curfew relaxed Mukesh gathered himself and set out to the godown whose address Neera had given him. Mukesh had been limping along the road when a patrol jeep accosted him and the personnel in it sternly asked him to go back to where he had come from.

'Isn't this the relaxation hour when people are allowed to come out for essential tasks?' Mukesh asked humbly.

'It is for essential purpose, not for loitering,' the police personnel snapped back.

'I am going to get food for my children sir,' said Mukesh.

The policeman lifted his baton and before Mukesh could realize he was hit on his side. The pain made him double over and fall on his knees.

'My children will die of hunger, Sahab,' Mukesh said, his hands folded, his tone appealing.

'Get lost or I will break all your bones, you junkie!' the policeman shouted.

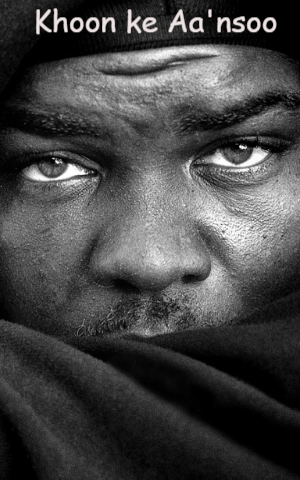

'I am not a junkie Sahab, you can talk to madam,' said Mukesh. His hands still folded he began to say Neera's mobile number. But the policeman was in no mood to relent. He hopped off his jeep and thrashed Mukesh within an inch of his life. When Mukesh reached home battered and bleeding he saw his wife sitting like a stone against the wall of their cuboid. Even upon seeing her husband's condition, she neither said anything nor so much as budged from her place. When Mukesh shuffled over to her and collapsed at her feet she calmly told him that Munna, their two-year-old son, did not wake up, nor ever will.

It took a while for Mukesh to process the information and when he finally did, two tears spilt out of his eyes and on their way down his cheek mixed with blood and turned red.